First published on http://kellygalbraithblog.com/2013/08/03/the-great-plague-fire-of-london-featuring-music-by-handel-part-rautavaara-tallis-mendelssohn/ 'Themes & Variations' by Kelly Galbraith

It seems every week or so when I listen to the radio or flip through the Globe and Mail, I am learning about a new super bug that has the potential to cut a large swath through the global village. Just this week the World Health Organization issued a warning about a disease named Middle-East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. The Sars outbreak in Toronto a few years back is a scary reminder of how easy it is to pass along a virus or bug which has its genesis in a remote region of China or Africa and ends up in a major urban airport and hospital. It is too easy to forget that for 300 of the last 400 years, civilization has been threatened by mass fatalities.

As I was watching the newscasts of the growing crowds gathering outside the London hospital waiting for the heir known as Prince George to make his long awaited arrival, the bottom of the TV screen showed other international headlines about yet a new virus with no known cure making its appearance. I thought about how easily it would be for a royal gawker who could be ill and not know it, and camped out for days to get that shot of the royal couple with babe in arms, to spread a virus. Today I am focusing my Themes & Variations blog, on England. Art does not happen in a vacuum. Much music and art is created during periods of enormous tragedy. England’s struggles produced some beautiful masterpieces.

The first outbreak of the plague known as Black Death was reported in China in the early 1330′s. In 1347, rat infested ships from China arrived in Sicily bringing the disease with them. Since Italy was the centre of European commerce, it didn’t take long for the disease to spread. Black Death was the most severe epidemic in human history. It killed entire families in days. At least 1000 villages were wiped out. It spread so rapidly that by 1350, one third of Europe was dead.

Geoffrey Chaucer lived in the second half of the 14th century. He knew only too well the devastation caused by Black Death. His tales tell of the thousands of medieval pilgrims who once trekked along the route from London to Canterbury in southeast England. They travelled on horseback and foot to the shrine of Thomas Becket in acts of piety and in search of miraculous healing.

Composer George Dyson’s setting of Chaucer’s text from his work ‘Canterbury Pilgrims’. “When that April with his showers sweet…then folks do long to go on pilgrimage. The holy blissful martyr for to seek that them hath holpen when they were sick."

Capriciossa – George Dyson; Canterbury pilgrims, Prologue

Vrouwenkoor Cappriciosa Amersfoort

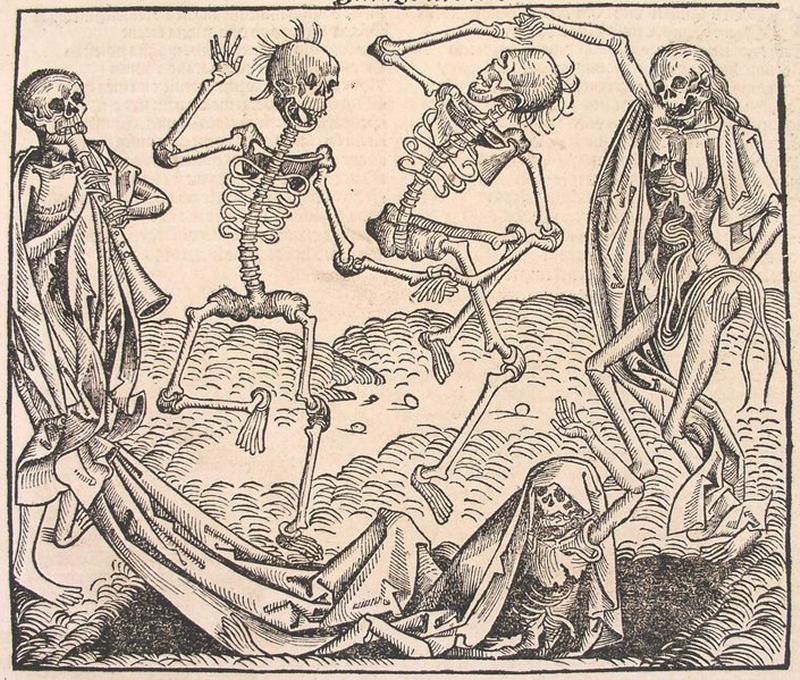

From 1347 until the 18th Century, England was subjected to periodic outbreaks of the plague. Before 1347, music was frequently heard through the streets. But after that, buskers didn’t appear as frequently. The exceptions were people who thought that they were probably going to die anyway so they might as well live life to the fullest and ‘Eat, drink, and be merry’.

“The art of dancing…is a commendable and rare quality fit for young gentlemen, if opportunity and civilly used. ….It is a quality that has been formerly honoured in the courts of princes, when performed by the most noble heroes of the times!”

JOHN PLAYFORD THE ENGLISH DANCING MASTER

Prince Rupert March and Masco

Odile Edouard (violin) Claire Michon (flutes & recorders)

Pascale Boquet (lute & baroque guitar)

And then it happened again! The Great Plague roared into London in 1665. People called it the Black Death, black for the colour of the dreaded lumps that appeared on their bodies, and death for the inevitable result. The germs were carried by fleas which lived as parasites on rats.

The spring of 1665 was particularly devastating for the poorer sections of London. By the time July came, which was very hot, and not a typical cool English summer, death was knocking at many a door, and panic was setting in. The roads were crowded with people fleeing London. By mid July, over 1,000 deaths per week were reported in the city. Rumours were spreading that the fleas on dogs and cats were the culprit so the Lord Mayor ordered all of them to be destroyed. 40,000 dogs and 200,000 cats were killed. The real effect of this was that there were fewer natural enemies of the rats who carried the plague fleas so the disease spread that much more rapidly. The rich nobility took off to their country estates, followed by the merchants and lawyers. Most of the clergy suddenly decided they could best minister to their flocks from far, far away.

Matthew Locke – How Doth the City Sit Solitary

If you were a doctor or had work that kept you in contact with plague victims, you had to carry a coloured staff so the people could avoid you. If a member of your family became sick, your house was sealed for 40 days. Forget about escaping for guards were posted at your door. By August 1665 there were over 6,000 deaths per week. It wasn’t until cold temperatures of winter settled in England that the plague’s grip was finally loosened.

George Frederic Handel: The Occasional Oratorio 'Hallelujah!'

Handel Consort

In February 1666 Charles II returned to London. The worst of the plague was over. Things were going to get better. They couldn’t get any worse, or so Londoners thought. Wrong. From the journals of John Evelyn and Samuel Pepys on September 2, 1666.

Nearly every housewife has made the same mistake, usually with no great consequence. But on September 2, 1666 the result was apocalyptic. Thomas Farrinor, baker to King Charles II of England, neglected, in effect, to turn off his oven. He thought the fire was out, he later claimed, but apparently the smoldering embers ignited some nearby firewood and by one o’clock in the morning, three hours after Farrinor went to bed, his house in Pudding Lane was in flames. Farrinor, along with his wife and daughter, and one servant, luckily escaped from the burning building through an upstairs window, but the baker’s maid paid dearly for his carelessness, becoming the Great Fire’s first victim.’

Arvo Pärt – Cantus in Memory of Benjamin Britten

from Album Tabula Rasa

“The fire then leapt across Fish Street Hill and engulfed the Star Inn. The London of 1666 was a city of half timbered, pitch-covered medieval buildings that ignited at the touch of a spark – and a strong wind on that September morning ensured that sparks flew everywhere.”

From the Inn, the fire spread into Thames Street, where riverfront warehouses were bursting with oil, tallow and other combustible goods. By now the fire had grown too fierce to combat with the crude firefighting methods of the day which consisted of little more than bucket brigades armed with wooden pails of water. The customary recourse during a fire of such magnitude was to demolish every building in the path of the flames in order to deprive the fire of fuel, but the city’s mayor hesitated, fearing the high cost of rebuilding. Meanwhile, the fire spread out of control, doing far more damage than the most overzealous firefighters could have managed.

Samuel Pepys wrote this reflection after a boat trip down the Thames:

‘Everybody was endeavouring to remove their goods, and flinging them into the river or bringing them into lighters; poor people staying in their houses till the fire touched them, and then running into boats. And the poor pigeons, I perceived were loath to leave their houses but hovered about the windows and balconies till they burned their wings and fell down…. With one’s face in the wind, you were almost burned with a shower of fire drops. This is very true, so that houses were burned by these drops and flakes of fire even when 3 or 4 nay 5 or 6 houses from each other. When we could endure no more at the water, we went to a little ale house on the Bankside and there saw the fire grow. So far as we could see up the hill of the city, in a horrible malicious bloody flame, not like the fine flame of an ordinary fire. We stayed till we saw the entire arch of the fire from this to the other side of London bridge and in a bow up the hill for an arch of above a mile long. It made me weep to see it – the churches, houses and all on fire and flaming at once, and a horrid noise made and the crackling of houses at their ruin.”

Einojuhani Rautavaara Cantus Arcticus - Melancholy, Swans Migrating

During this period of the plague and great fire, Londoners did create magnificent art. The world no doubt lost many talents and dreams but some of the world’s greatest artists did survive. Henry Purcell was a boy beginning his musical training. Daniel Defoe would write a book on the plague but also pen ‘Robinson Crusoe’

Composer Matthew Locke wrote many works for church and state. John Milton wrote ‘Paradise Lost’. And London had to be restored and St. Paul’s Cathedral had to be rebuilt. This new Cathedral, the masterpiece of Sir Christopher Wren was to become the home to William Boyce, Maurice Greene, Thomas Attwood and Sir John Goss, each of whom held the post of organist at the Cathedral and wrote glorious music for that spacious acoustic.

St. Paul Cathedral (London – XVII – XVIII Century AD) England

Thomas Tallis: ‘If ye love me, keep my commandments’ Cambridge Singers dir.: John Rutter

Salva nos 1 – 2 (from Salvator Mundi – antiphon for 5 voices) The Tallis Scholars

Felix Mendelssohn was a highly popular figure in the English musical scene. He made no fewer than ten visits and during one of them, his oratorio ‘Elijah‘ received its first performance at St. Paul’s Cathedral.

Mendelssohn: Elias Chorus ‘Hilf Herr!’

Christine Schäfer, soprano. Cornelia Kallisch, alto. Michael Schade, tenor. Wolfgang Schöne, baritone. Gächinger Kantorei Stuttgart. Bach-Collegium Stuttgart. Helmuth Rilling, conductor

http://www.beautifulbritain.co.uk/htm/outandabout/eyam.htm